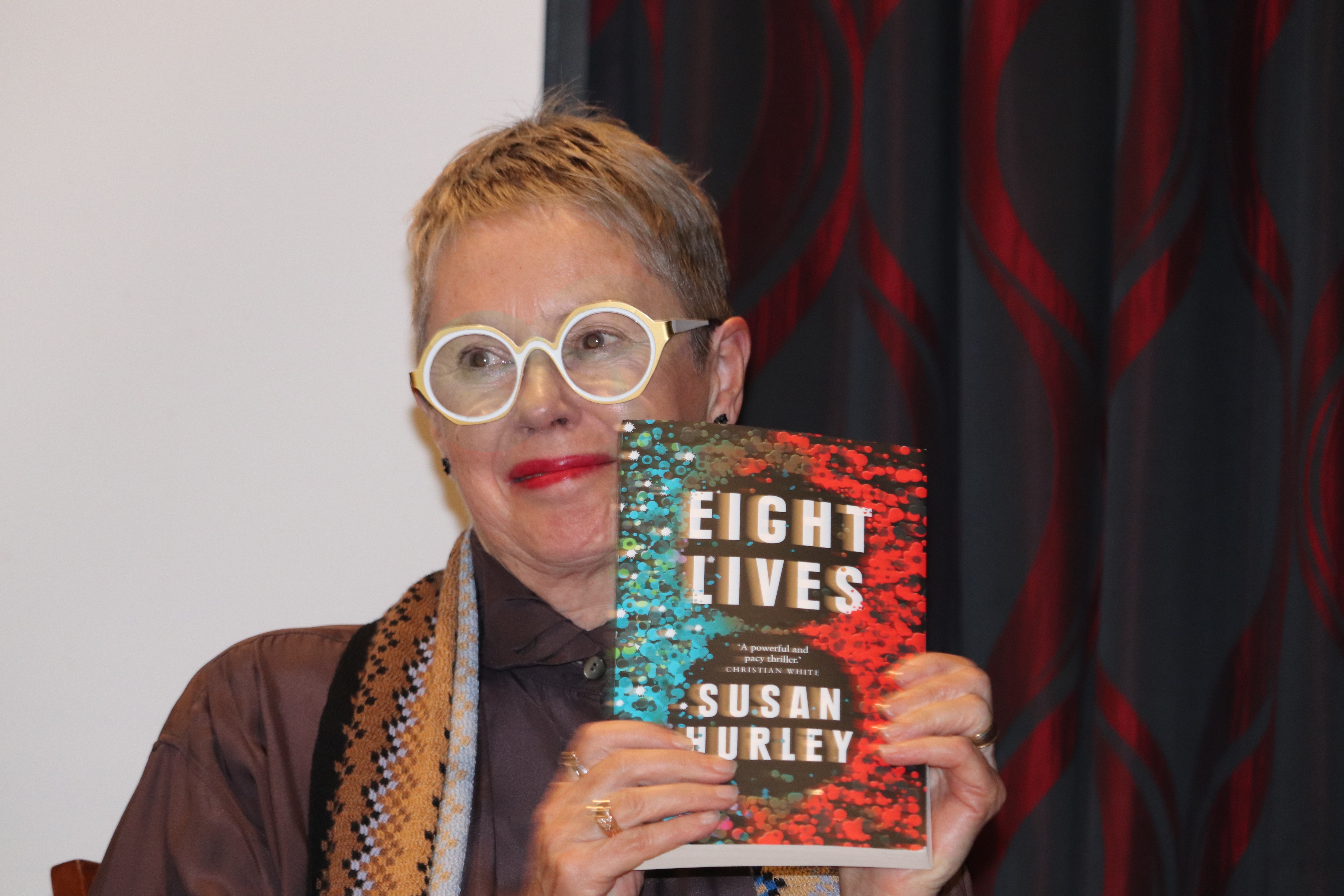

Robyn Walton, Vice-President of Sisters in Crime Australia, talks to Dr Susan Hurley, about her amazingly topical novel, Eight Lives (Affirm Press, 2019), and the science that underpins it.

So, Susan, in Eight Lives the US government stockpiles 30 million doses of Pandaid, a treatment for a pandemic virus, at a cost of $1.5 billion in case an influenza pandemic occurs. How did you come up with such a scenario?

Epidemiologists have been warning for years about the likelihood of another pandemic, similar in severity to the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. My PhD was in epidemiology and health economics, so I was aware of the warnings, and at one point I even did some work on pandemic planning. Stockpiling of treatments and protective gear was something that we talked about. But it’s expensive and complicated. For example, when I did the pandemic work, I purchased a few packs of masks and a stock of alcohol gel as a personal precaution. That was more than 10 years ago. When Covid-19 emerged, I retrieved my stockpile from basement storage. The masks’ elastic ties had perished and the antiseptic gel was out of date!

Your novel had its origins in a real-life drug trial. Tell us about that trial.

It was the first human trial of a new drug and it took place in London in 2006. The drug had been hailed as a potentially ground-breaking treatment for diseases of the immune system. Eight healthy men volunteered. Unfortunately, the six men who received the drug all suffered the same severe inflammatory reaction. They were apparently writhing in pain, they swelled up – one man’s head ballooned to such an extent that he was described as the elephant man – and they suffered respiratory and kidney failure. They had to be admitted to Intensive Care and were put on life support. The reaction was a cytokine storm.

We’ve heard that term ‘cytokine storm’ in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic too haven’t we?

Yes. In a cytokine storm the body’s immune system smelts down. Hundreds of proteins called cytokines are released and they start attacking the body’s own cells. Cytokine storm often occurs during fatal influenza virus infections and there have been reports of it happening to patients with severe Covid-19 infections too.

What made you think that a disastrous drug trial would be a good starting point for a novel?

The first trial of a drug in humans is an inherently dramatic moment. No matter how comprehensive the preceding animal studies, scientists can’t predict with certainty how humans will react to a drug. Trials are a step into the unknown, and the London trial wasn’t the first (and won’t be the last) to end tragically.

There’s a lot at stake too: the health and lives of the participants, the drug researchers’ careers, and the money that the biotech and pharmaceutical companies have invested in developing the drug.

The fact that there’s a moral grey area in terms of who risks their life in these trials made the idea of a novel pivoting around a trial even more interesting. The people who volunteer for trials aren’t the ones who stand to gain if the trial is a success.

In John le Carre’s The Constant Gardener, for example, the trial participants were poor people from Kenya. And trials have been conducted in those settings in real life. In the London trial, the volunteers were perfectly healthy men who needed money. One was an out-of-work actor who needed to clear some debts. The men were each paid 2,000 pounds. Fortunately, they survived the reaction. But they were in hospital for months, one lost fingers and toes due to gangrene, and there have been suggestions that damage to their immune systems will be lifelong. In contrast, the biotech company behind the drug declared bankruptcy. It couldn’t be sued.

I also like reading novels that are about ‘something’ in addition to the characters and the story. Robert Harris’s The Conclave, for example, is a terrific thriller about the selection of a new Pope. Reading it, I learned a lot about the Catholic Church. So, I wanted to write a novel that took readers to an unfamiliar world – the world of drug development, a world that affects everyone but few know much about. Eight Lives gives readers the opportunity to learn about testing of new medicines and a new class of treatments called monoclonal antibodies. If they’re not interested – no problem, they can just skim the science bits!

Your plot is ingenious, and I don’t want to give spoilers, but do you mind telling us about your five narrating characters, the communities they move around in, and how they relate to your central researcher, David Tran aka Dung Pham?

Your plot is ingenious, and I don’t want to give spoilers, but do you mind telling us about your five narrating characters, the communities they move around in, and how they relate to your central researcher, David Tran aka Dung Pham?

Eight Lives is set in Melbourne. It’s David Tran’s story. Once a refugee, he’s now a brilliant doctor who has invented a potential blockbuster drug. At the start of the novel, the reader is told that he dies. The first mystery is how: how did he die? When that question is answered the mystery becomes why: why did he die, who’s responsible and who will be punished?

Five characters serve as the narrators, with little snippets from David himself. The narrators each tell how they solve the mystery of David’s death, or work to conceal what they know happened, or try to hide the part they played. They’re from different parts of David’s life. Two are family, one is a childhood friend, and two are from David’s work life.

Rosa Giannini is one of the characters from David’s work life. She’s his junior research assistant and she provides the spine of the story. She’s a newcomer to the science world and to the educated class of Melbourne. She’s an Italian immigrant who’s lived most of her life in the Australian bush. I see Rosa as the brains of the story, but she makes mistakes and, as a consequence of David’s death, it looks like her longed-for career as a scientist won’t happen.

Then there’s Miles Southcott, David’s childhood friend, who’s now a failed professional tennis player and a failing doctor. He’s possibly my favourite character. Miles, or Milesy as his Mother calls him, is from the born-to-rule class, someone you might encounter in Melbourne’s Collins Street having a coffee with his young investment banker mates. But Miles is very self-aware. He’s a self-confessed slacker who made a Faustian bargain with David when they were teenagers. His future is also at risk after David dies.

The other character from David’s work life is Foxy. He’s a fixer for David’s business associates and other one-percenters. When their kids or businesses go bad, he washes away the inconvenient facts, he buries the bodies, sans drama and with the utmost discretion, as he says in the novel. He’s someone who, when the house catches on fire, blames the furniture rather than the person who was smoking in bed. And he’s very pretentious, breaking into snippets of French.

David’s family is represented by Abigail, his girlfriend. She’s the conscience of the story. Abigail is trying to live a good, moral life, but she’s finding it hard.

And finally, there’s Ly, otherwise known as Natalie, David’s sister, a street-smart young woman who adores her brother. She’s a character who I hope readers’ hearts go out to. Mine certainly does.

Your knowledge comes from a working life spent in medical research, the pharmaceutical industry, and public health programs. Please tell us a little about your research interests and how they inform your thoughts about reactions to the COVID 19 emergency.

My main area of work and research has been cost-effectiveness analysis. I’ve looked at the costs and benefits of medicines and written submissions to get new medicines subsidised on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. I’ve also analysed the cost-effectiveness of public health interventions, including HIV prevention strategies, mammographic screening, smoking cessation programs and vaccines. I ‘ve done that work for the government as well as not-for-profits, such as the Cancer Council.

Cost-effectiveness analysis is all about the fact that it’s not enough for a medicine to be effective. Our government will only fund a new drug if its benefits justify its price. Similarly, with public health and safety initiatives. Think of road safety. If we banned driving or lowered the speed limit to, say, 5 km/hour, road fatalities would be dramatically reduced. But the costs in terms of moving goods around and getting people from A to B would be enormous. Road safety regulations like that aren’t regarded as cost-effective, so we don’t implement them, even though they would save lives.

So, in relation to the Covid 19 emergency, I’ve been surprised to hear people such as the Governor of New York say that we can’t put a value on a human life. In other words, every life has to be saved, no matter what the cost. That’s not how governments have worked in the past. With Covid 19 the deaths are very visible, though. So governments have been prepared to pay a very high cost in terms of productivity lost, in order to save lives. Health economists are going to be analysing this for years to come.

What prompted you to begin writing fiction?

I’ve always loved reading, and writing a novel has been a lifelong dream. One day I decided to get on with it.

Finally, I hear you have a work in progress. A second novel?

Before the coronavirus pandemic I started working on a novel that involves a virus jumping from an animal species to humans, with some help from scientists!

Thanks, Susan, especially for the time and effort you’ve given to explaining some of the scientific and economic realities of immunology.

Click here for more info. You can order a hard copy from The Sun Bookshop.