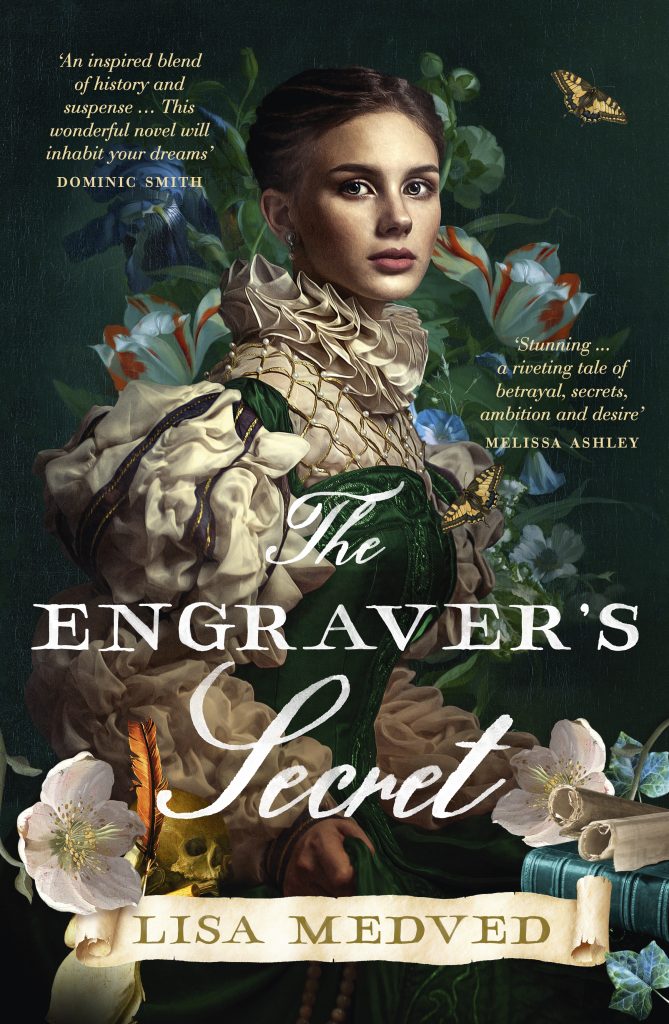

For the April Author Spotlight, Natalie Conyer, spoke to Lisa Medved about her debut novel, The Engraver’s Secret. Lisa, an Australian author, lives in the Haque but will be visiting Australia and speaking at Sisters in Crime’s Melbourne event, Reimaging the Sleuth, on Friday 19 April, 8 pm.

Natalie says that you’d hardly know that The Engraver’s Secret is Lisa Medved’s debut novel: it’s a complex mix of art and crime, a novel about families, and an exciting what-if mystery. The story, set in Antwerp, oscillates between the seventeenth and twenty-first centuries, and centres on two women: Antonia Vorsterman, daughter of an engraver; and Charlotte Hubert, art historian, and Rubens expert. The link between them begins with a letter hidden in an ancient map folio. When Charlotte discovers this letter and follows its trail, she’s led to betrayal, violence – and love.

The Dutch translation of your book was published in Belgium as De Graveur in February 2022 and was called a thriller. The book is also considered a crime story and historical mystery and has elements of romance and family drama. Did you set out to create a multi-genre novel when you began writing The Engraver’s Secret?

The process of writing The Engraver’s Secret has been rather convoluted, but very exciting. I completed the first draft in 2015 and it was an action-packed, modern-day crime story. But I wanted it to have more layers of interest, for the plot to have more thought-provoking elements, and the characters to be more compelling.

As I redrafted the story, I strengthened the historic elements, emphasised the seventeenth-century part of the story, and contrasted the differences between the two eras. As I developed the plot and characters, various themes emerged: ambition and ownership, trust and betrayal, family connections, and control. All of these contributed to making it a multi-genre story with strong elements of crime, mystery, family drama in an historical and modern-day setting.

The Engraver’s Secret is complex in its use of split timelines – it moves across centuries – and parallel themes, the entwining of an art mystery with accounts of family betrayals. What challenges did this complexity pose for you, and how did you solve them?

I’ve always enjoyed reading dual-timeline novels because it allows me to experience a story from two different perspectives. It’s like being at a party where you interact with guests in the garden, then you move inside the house to chat with other people, and discover the two conversations are related. Different people, different viewpoints, same story. Or are they? Perhaps they’re different stories but with strong connections.

Experimenting with such interconnections is one of the reasons I enjoy writing dual timelines. It allows me to pose questions in one timeline then see how they relate to another, reveal the actions and motives of one character then link them to another character, decades or centuries apart.

Keeping the reader interested in two stories simultaneously is the main challenge when writing a dual-timeline story. Each timeline needs enough forward momentum and pacing, enough links between the two stories, and enough questions about the past and future, to make the novel intriguing. At the same time, there can’t be too many questions, otherwise the reader may become confused or overwhelmed.

I write one timeline in full, then the second, which allows me to completely focus on one set of characters and era at a time. In subsequent drafts, I piece together the two stories like a jigsaw puzzle, providing links between certain events, characters, themes, locations, and even objects.

While writing, I develop a large spreadsheet to help organise the various parts of the story and show their connections. The spreadsheet includes a brief description of each chapter, which characters are present or mentioned, key themes, relevant dates or times, focal objects – for example, a seventeenth-century map folio – and also the questions posed at the close of each chapter. These include mystery questions about events that have occurred in the past, and suspense questions about what may happen next. Hopefully, by the end of the story, the main questions are resolved.

I also rely on trusted beta readers and editors who read the manuscript with fresh eyes and point out any parts of the story that may be confusing or too complicated, or places where the links are either too vague or too obvious. Finding the balance is the main challenge.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

The idea for The Engraver’s Secret came to me about ten years ago when I visited the Rubenshuis in Antwerp, the former home of Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens. An engraving by his chief engraver, Lucas Vorsterman, was on display alongside a brief description, which suggested the two men were close and then had a falling out.

Intrigued, I did some research and came upon a little-known story about a disagreement over who owned the original copper engraving plates and who had the right to reproduce the images. Intellectual property wasn’t widely considered in early seventeenth-century Flanders. I began dreaming up a story about lost seventeenth-century treasures and a modern-day academic trying to discover their whereabouts.

Art museums and historical places in Antwerp were especially inspirational for me when writing the story. The Plantin-Moretus Printing Museum, where Rubens and Vorsterman both worked early in their careers, is on the UNESCO heritage list and filled with amazing objects. Saint Catherine’s Begijnhof, similar to a convent and now turned into private housing, inspired one of the key locations for the modern timeline.

While browsing in an antique shop in northern France, I saw a tattered leather-bound folio filled with extraordinary old maps of Europe, including several maps with faint pencil marks showing someone’s journey from long ago. It gave me the idea to include a seventeenth-century map folio in the story.

I’ve always had a fascination with the secrets that can lie beneath the surface of family dynamics, so this was another strong inspiration for me. Relationships between people are what give emotion and depth to a story, rather than just action-packed sequences. I decided to contrast two father-daughter relationships, one in the seventeenth century and one in modern times, as the basis of the main relationship in the story. I wanted the story to revolve around family secrets, the devastating consequences that can occur when secrets remain hidden, and the struggles that happen when loyalty is questioned and trust is broken.

The Engraver’s Secret is obviously the result of extensive and detailed research. I know you have a degree in fine art and history, but what research did you do for this book, and how did you do it?

During the seven to eight years I spent writing The Engraver’s Secret, I completed masses of research before I started writing and also while writing. The search engine on my computer was constantly open, along with etymology websites to check the accuracy of words and objects for specific times or places. If cobalt blue pigment wasn’t invented until 1803, for example, I didn’t use the term in the seventeenth-century timeline but rather used the more accurate terms of ultramarine or smalt.

I researched the history of seventeenth-century Flanders, the customs of its citizens, the influences of the Spanish Hapsburg court, and tensions between Protestants and Catholics. I recalled my university studies in history and fine art and researched the art and lives of Rubens, Vorsterman, Jan Brueghel, Frans Synders, Clara Peeters, and their peers. I studied the maps of cartographers Frederik de Wit and Abraham Ortelius. I learnt about goffering irons to crimp the ruffled collars worn by the well-to-do, and pattens to protect the shoes as they walked along muddy streets. Were potatoes or turnips more common in the markets of 1621 Antwerp? When did soft lace collars become more popular than huge, starched ruffs? Was the term ‘copyright’ known in early seventeenth-century Flanders?

I studied non-fiction books during my research, especially Rubens: A Portrait by Paul Oppenheimer (2002), which was particularly useful in learning about Rubens and his relationship with Vorsterman. I accessed the Rubenianum Institute’s online catalogue to read excerpts of the Ludwig Burchard Online collection, which provided fascinating insights into the work and life of Rubens.

For the modern-day timeline, I researched art conservation techniques, academic theft, religious institutions, and the villages of Flanders. I learned masses of information about the two time periods, but I was very selective as to which details I included in the story. My story, after all, is a work of fiction, not a history book, and I didn’t want it to be overfilled with dry information. The facts I learned were used to flavour the story.

The story is set in Antwerp, a city you know well. What attracted you to using this setting, and how did you use your lived experience to bring it to life?

Having majored in fine art and history at university, I was familiar with the art of Rubens and the history of this corner of Europe. Peter Paul Rubens was a fascinating multi-talented artist and diplomat who used his connections in royal courts across Europe to promote his creative talents and manage his busy workshop of apprentices and assistants. Although he travelled extensively, his home was in Antwerp where he renovated a Flemish townhouse and added an Italianate-style extension.

The early seventeenth century was dramatic and tense, filled with religious conflict, border skirmishes, trade sanctions, the Eighty Years’ War, and Flanders (modern-day Belgium) ruled by the Spanish Hapsburg court. Throw into this mix a violent conflict between a famous painter and his little-known engraver, the setting was a perfect choice for me to spin my story.

I’ve been fortunate to have lived in Europe for the past sixteen years, so it was easy for me to catch a train from The Hague and arrive in Antwerp eighty minutes later. When I needed a break from sitting in front of my computer, I visited other places in Belgium to explore old city centres, cobblestone streets, and historic buildings to get a feel for the era and history.

During one of my day trips to Antwerp, I discovered the city’s beautiful Begijnhof, founded in 1544 where single women lived as a religious community. Although begijnen have not lived there for many decades and the buildings are now used as private housing, I used some artistic licence to create a group of modern-day begijnen living there for my story. The Begijnhof is such a peaceful place, which contrasted perfectly with my characters who become caught up in a dangerous search for lost treasures.

Finally, could you tell us something about your work in progress, which according to your bio is set in fin-de-siècle Vienna and post-World War I London, and focuses on Gustav Klimt?

For my second novel, I’ve turned to the art, life, and times of Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt and fin-de-siècle Vienna. The story focuses on two women with a linked past, both searching for where they belong in the world.

The story of Lily begins in the closing years of the nineteenth century in Vienna, when socio-political upheavals and the growth of Modernism cause everybody, from rulers to commoners, to question their place in the emerging new century. Lily’s story moves between Vienna and the tranquil lakes of the Salzkammergut region where peace becomes a distant memory as the horrors of the Great War and Spanish Flu epidemic take hold, spinning everyone’s life out of control.

Intertwined with Lily’s narrative is the story of Fenna, who lives in 1932 London. Exploring her past, fearful for her future, searching for her sense of identity and belonging, Fenna’s story moves from London to her birthplace of Amsterdam, then travels to Munich and finally Vienna. For Fenna, it is a gradual unravelling of her shared past with Lily and the artist Gustav Klimt.

My second novel will be published by HarperCollins Australia in 2025.

More info here.