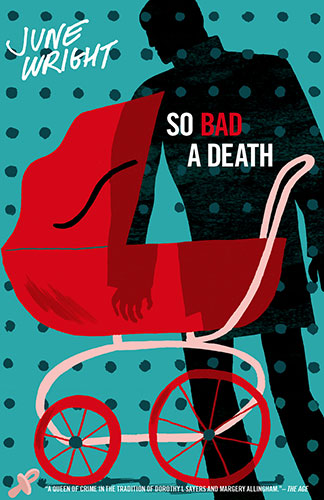

Author: June Wright

Publisher: Verse Chorus Press

Copyright Year: 1949 first published; 2015 re-issued with introduction and interview transcript by Lucy Sussex

Review By: Robyn Walton

Book Synopsis:

The return of Maggie Byrnes, heroine of Murder in the Telephone Exchange, finds her married, with a young son, and living in an outer Melbourne suburb. But violent death dogs her footsteps even in apparently tranquil Middleburn. It’s perhaps not that much of a surprise when widely disliked local bigwig James Holland (who also happens to be Maggie’s landlord) is shot, but Maggie suspects that someone is also trying to poison the infant who is his heir, and turns sleuth once more to uncover the culprits. First published in 1949, So Bad a Death is June Wright’s second novel, which she originally planned to call Who Would Murder a Baby? Her publishers demurred, but under any title it’s a worthy sequel to Murder in the Telephone Exchange. Novelist and crime fiction historian Lucy Sussex contributes an introduction to this reissue, which also includes a revealing interview she conducted with June Wright in 1996.

In So Bad a Death, the sequel to June Wright’s 1948 Murder in the Telephone Exchange, feisty protagonist Maggie returns to risk her life solving another crime committed in her own back yard. Wright ingeniously and unapologetically applies English ‘Golden Age’ murder mystery conventions to mid-twentieth century Australian scenarios in both novels. To this extent the books are intellectual exercises; they go beyond the simple model of the puzzle-entertainment to remark inter alia on social change and the questionable suitability of older literary modes in a postcolonial nation growing away from Britain. The enclosed, ‘cosy’ setting in So Bad a Death is a baronial-style estate on the edge of metropolitan Melbourne. In the post-War, ‘baby boom’ years, buyable housing is in short supply and young couples are shifting further from the inner suburbs, the men commuting to city jobs, the women experiencing stay-at-home motherhood and housekeeping duties with varying degrees of satisfaction. Wright tells it how it is from first-hand experience, having moved to the then outlying suburb of Ashburton, the model for her fictional Middleburn, with her husband and young children. Her murder victim occupies a mansion modelled on an actual property in the Ashburton area.

For decades James Holland has dominated and manipulated his household and estate, the village, local business people and professionals, and the adjoining streets of residences, as well as affairs at his pastoral property. Thus there is no lack of suspects when the ‘Squire’ is found dead after having failed to turn up for a dinner party he was to host at Holland Hall. Wright wrangles her cast of characters with skill, keeping them distinct from each other and clearly enjoying indulging in a fair amount of caricature and social satire. In Murder in the Telephone Exchange Murder Wright worked within a smaller compass. Sherequired the reader to pay attention to minutiae inside the exchange building – workers’ shifts, telephony equipment, lengths of calls, coded notes, special roles and rooms – while the suspects were all people who worked at the exchange (until a golfing businessman was introduced late in the piece). I found that novel a test of patience even though Wright was clever in choreographing her characters’ doings down to the split second. In So Bad a Death, however,Wright allows herself a slightly broader range of movement, and although there are again some telling details – flashing lights from the Hall’s tower, dodgy phone communications, the timing of a telegram – a diversity of psychological and financial motivations is also brought into play from the outset. As in Murder in the Telephone Exchange Murder and a host of English novels, the solution has much to do with disclosure of secret identities and deceased characters’ intimate past doings in other places.

With both novels told in the first person, the reader spends a lot of time in Maggie’s company, so how greatly you enjoy these books will largely depend upon how much you like Maggie and how far you can empathise with Maggie’s situation in life. The Maggie of 1949 is as bold as she was in the first, 1948 novel. With plenty of dialogue carrying the narrative, she shows off her straight-talking investigative method and sometimes tart, sometimes facetious manner on almost every page. Provided you can tolerate some dated expressions and attitudes, you’re likely to find the effect quite bracing.

Here’s a sample:

“I meant to cut you dead the next time we met,” I informed him, “out of revenge for what you did last night.”

For a moment my words might have been calamitous for the unnerving effect they had on Ernest Mulqueen. Then it penetrated that I was teasing him […]

“Your hair was done differently,” he tried to defend himself.

“No go. I always wear the same style for months on end.”

I felt like someone staring through a magnifying glass at a moth on the end of a pin. And yet I could not stop myself. […]

“You either wanted to snub me or else you had something on your mind.”

My words were daring under the circumstances, in spite of a light tone. I felt a little frightened after I had spoken: colour flowed into Ernest Mulqueen’s face. It was not his original ruddy colour but a flush of temper. He half raised a clenched fist.

The diction of Maggie’s policeman husband John is stilted, but fortunately he doesn’t speak often, except in the final chapter, the classic explanatory coda. Ultimately it does not greatly matter which puppet person did which dastardly deed: the achievement is in the confidence and verve with which the author orchestrates the many voices and scenes throughout her novel.

In So Bad a Death Wright achieved what she (apparently) set out to do. Yet she did not publish any more Maggie stories. This reader was left with the sense that, although the author had created a snappy, smart-mouthed character with the potential for further adventures, Wright did not derive sufficient satisfaction from the contrived nature of this kind of detection writing to want to go on doing it indefinitely. Under the “light tone” Maggie believes she deploys, the author is labouring and is wondering whether all the effort is worth the outcome. Wright did publish a crime series with a nun protagonist later on; I look forward to reading those novels (also reissued by Verse Chorus Press) to see whether the tone is different.